ISS – Portland – Part V: Discussion – Meaning: Politics, Consequences, Work?

August 5, 2016

Announcing The Abeng: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Criticism

August 19, 2016Scriptures Contemporary Relevance

Editor’s Note: “Scripturalization: A Primer” is part of our ongoing project to explore and exemplify the human practice of scripture-making for a general audience. For more than a decade ISS has sponsored research projects and facilitated conversations that have expanded, and in some cases exploded, our understanding of “scriptures.” Though this work takes a variety of forms, the most comprehensive treatment to date on the subject has been that of the institute’s founder and current director, Vincent L. Wimbush. “Scripturalization” is his term for the complex and ineluctable “social-psychological-political” matrix that “establishes its own reality” through language play, and its formulation signifies a lifetime of wrestling with the central problems of the modern world. The primer is our effort to introduce his still evolving theory to a wider audience, by exploring its composite arguments, historical antecedents, and theoretical implications.

The ISS research agenda, though broad, is organized around the examination of the human practice of making texts mean something essential to a given community. This tendency to “scripturalize” is deeply historical, and at this point in the development of human civilizations, nearly universal. As professor of religion Wilfred Cantwell Smith described in his book, What Is Scripture? (1993), “it emerges that being scripture is not a quality inherent in a given text, or type of text, so much as an interactive relation between that text and a community of persons… One might even speak of a widespread tendency to treat texts in a ‘scripture-like’ way: a human propensity to scripturalize.”

The ISS research agenda, though broad, is organized around the examination of the human practice of making texts mean something essential to a given community. This tendency to “scripturalize” is deeply historical, and at this point in the development of human civilizations, nearly universal. As professor of religion Wilfred Cantwell Smith described in his book, What Is Scripture? (1993), “it emerges that being scripture is not a quality inherent in a given text, or type of text, so much as an interactive relation between that text and a community of persons… One might even speak of a widespread tendency to treat texts in a ‘scripture-like’ way: a human propensity to scripturalize.”

Where the work of W.C. Smith leaves off, the Institute for Signifying Scriptures begins, examining the complex dynamics of the communities that transubstantiate texts into scriptures. The institute and its many affiliate researchers ask a variety of questions about scriptures and scripture making. Who, for example, is served by the sanctioned modes of scriptural interpretation? How can, for example, something like the Christian bible be used to justify slavery, and liberation? The Quran, stoning and mercy?

Following these questions, it might seem natural to conclude that scripture is simply a cypher for communal self-interest. Certainly many scientists, cynics, and atheists would make this claim. It’s also not very far from what Karl Marx thought. We, however, think there’s more to the story.

We believe that although it is important to acknowledge the self-serving nature of scriptural interpretations, this sort of off-the-cuff dismissal of “scriptures” misses far too much. Why, after all, is this the contended ground? Why recur to a scripture to justify a course of action? Why fight over the “original” intent of a document?

If you would, stop for a moment and think about that. Why return to a scripture to legitimize a current course of action?

The immediate answer that might occur to you is that scripture is used in this way because a religious community believes that some given scripture is holy, eternal, divinely inspired, perhaps even infallible. That’s a good place to start, but it doesn’t get us very far. Let me give you a contemporary example that illustrates why.

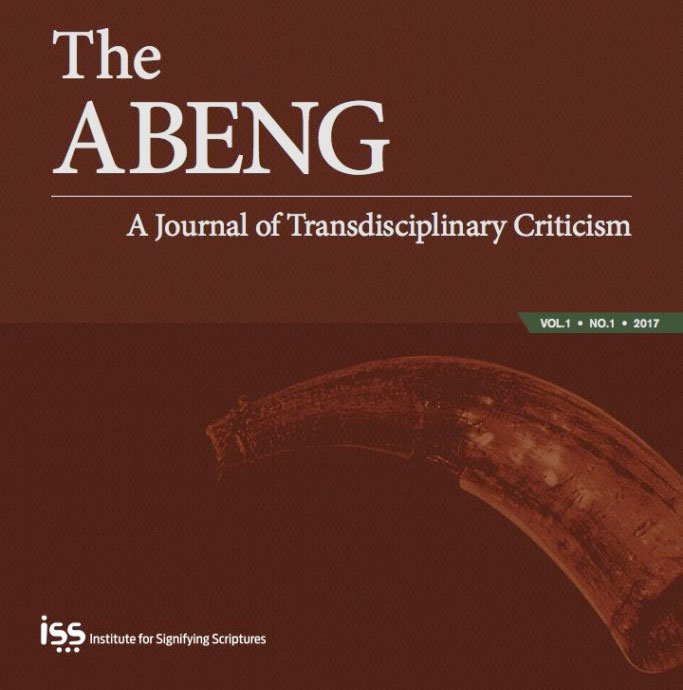

On July 28th, 2016 Khizr Khan, father of the slain U.S. Army Captain, and Muslim, Humayun Khan, delivered his now famous rebuke of U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump. He did so by appealing to common decency, and his own personal story of sacrifice, but the moment widely regarded as the most powerful, was when Mr. Khan reached into his inside breast pocket, and pulled out his copy of the U.S. constitution, as he said, “Let me ask you: have you even read the United States constitution? I will gladly lend you my copy. In this document, look for the words ‘liberty’ and ‘equal protection of law’.

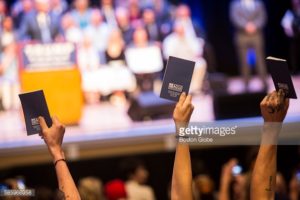

This gesture caught on, and following Mr. Khan’s speech, protestors used pocket constitutions as a form of protest at a Donald Trump rally in Portland, Maine, and according to Kim Soffen of the Washington Post, “a $1 edition of the pocket Constitution printed by the nonpartisan National Center for Constitutional Studies became the second-bestselling book on Amazon.”

This gesture caught on, and following Mr. Khan’s speech, protestors used pocket constitutions as a form of protest at a Donald Trump rally in Portland, Maine, and according to Kim Soffen of the Washington Post, “a $1 edition of the pocket Constitution printed by the nonpartisan National Center for Constitutional Studies became the second-bestselling book on Amazon.”

What did this gesture mean? Were these protestors making a legal argument? Something like, “Donald Trump, you really should read the 14th amendment’s equal protection clause.” Or, “Trump doesn’t understand the separation of church and state.”

Was Khizr Khan, for all of his emotional vigor, simply informing the nation that Donald Trump was ignorant of the law?

In a sense, you could reasonably argue that both of the above approximate some part of what was being communicated, but this would miss the potency of the gesture. Holding our national scripture aloft, while denouncing Trump, gave Mr. Khan’s challenge the weight of an ex cathedra encyclical. He was in effect saying that Donald Trump was an apostate, un- American; he was ignorant of our holy writ.

Yet, barring certain syncretic Mormon beliefs, the mainstream account of our founding document is not one of divine inspiration, but human aspiration. In other words, the importance of scripture isn’t confined to the “religious” sphere alone.

Is it coincidental that Khan’s criticism of Trump was the first one to seriously damage the candidate beyond the 24-hour news cycle? Perhaps. Indeed, it shouldn’t be discounted that Trump also drew rebuke for his flippant treatment of the Khan’s blood sacrifice—their son’s vital forfeiture to the American ideal.

Still, the image of Khan brandishing the constitution refracts the story surrounding his DNC appearance like a stained glass window. Here’re the top six Google search image results for “Khizr Khan”—as of August 15th, 2016.

What else should we call the potency of this display, but scriptural?

This is just one contemporary example among countless others—some trivial and some terrible. Please look for future updates to our primer for other examples, and historical explorations, and, as always, feel free to leave a comment below. We welcome questions and challenges.