The Abeng | vol 4, no.1

May 19, 2020

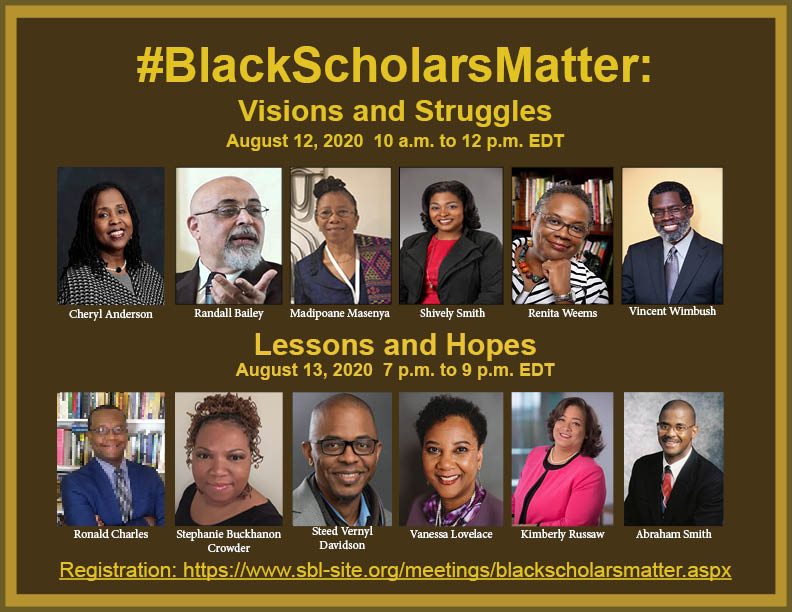

#BlackScholarsMatter

July 16, 2020American Constantine

June 2, 2020

“Ah, Constantine, how much evil you gave birth to, not in your conversion, but in that Donation.” So wrote Dante (Inferno, Canto 19) in the fourteenth century about the fabrication, the “fake news,” that helped consolidate and justify the worldly power of “the Church,” now the churches (with the Reformation as refractions of social, ideological, economic, and political formations) in the history of the western colonial and even post-colonial world. The idea of the “donation” turned around the “fake” notion that the emperor of the fourth century Constantine had granted or handed over to the church some of the worldly or political authority and power then thought “naturally” invested in the emperor. Naturalization of such fabrication required strategic and careful and sustained manipulation of what cultural critic Michel Foucault called “discourse,” freighted shorthand for signs, symbols, images, texts (scriptures). Foucault also aptly and pointedly argued that “discourse” represented weapons of manipulation toward naturalization, a kind of “violence we do”—to things and each other.

President Donald J. Trump walks from the White House Monday evening, June 1, 2020, to St. John’s Episcopal Church, known as the church of Presidents’s, that was damaged by fire during demonstrations in nearby LaFayette Square Sunday evening. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

Yesterday, in Washington, D.C., Donald Trump made himself an American Constantine by performing for us what I should like to name American scripturalization—a violent regime of signs and symbols, scriptures. Crass, classless, creepy—his performance of mimetic scripturalization, of the regime already firmly sedimented, was all of these. In front of St. John’ Church—an easily recognized site-symbol of the American nexus of church and state as registration of power, our clownish American Constantine per-form-ed religious “scriptures” through the office already granted him by political “scriptures” (the Constitution). As our American Constantine redivivus he thereby appeared with his awkward handling and showcasing of the (U.S. protestant-inflected already sanctioned, made dominant or authoritative by dominant figures and formations) scriptures to “donate,” to arrogate—(back) to himself!—the authority or power of the religious sphere.

The entire performance–of American-style mimetic scripturalization–was so hapless, so simplistic, so much the atmospherics set up by the carnival-barker, the reality TV persona, that Trump has paradoxically and (as usual) unwittingly provided opportunity for critical thinking about how such fabrications and naturalizations have worked and continue to work as a kind violence in the modern world. Normally such “white men’s magic,” as I have preferred to call it, with its scripturalizations/naturalizations/hierarchicalizations of race, gender, class, and so forth–requires a bit more behind-the-curtains work, complete with occluding rites and obscuring exegesis. But with this most recent mimetic stunt our American Constantine has shocked many to the core, provoking harrumphs from all quarters and in all sorts of media and genres—in amorphous odes to love as alternative; in all too expected (self-styled liberal) churchly denunciations; in political-tribal denials and/or loud silences. This is because the stunt lowered the threshold for discerning the work of the magic: it helps us to see how ridiculous and how fragile and “fake” all of it is. And it provokes us into considering how important it is going forward to put focus not on exegesis but on deep and wide (critical trans-disciplinary) excavation–of the psycho-social-patho-logics and politics of the phenomenon and dynamics of the performance of the scriptural, the regime of scripturalization. Only sustained focus on the problematics of the latter will help us understand how we have been scripturalized, the deep wounding effects of scripturalization, what we are as a scriptural formation; and how we have come naturally to “read”—black bodies (on the streets and elsewhere); and the gestures and otherwise incoherent soundings (from our performing reader-in-chief), as examples we cannot and must not avoid these days–on rather consequential terms.

Constantine, Constantine, how much evil we have enabled you to do!

—————-

Vincent L. Wimbush, Ph.D., is a scholar of religion and is currently director of an independent trans-disciplinary research organization called The Institute for Signifying Scriptures.